Self-healing solar in space

ASU researcher earns prestigious Air Force Young Investigator Award to advance next-generation space power materials

For the past 15 years, the ultrathin, low-cost solar-absorbing material known as perovskite has dazzled researchers with its potential to make solar cells more efficient. However, perovskite’s lack of operational stability and environmental sensitivity have kept it from leaping into everyday devices.

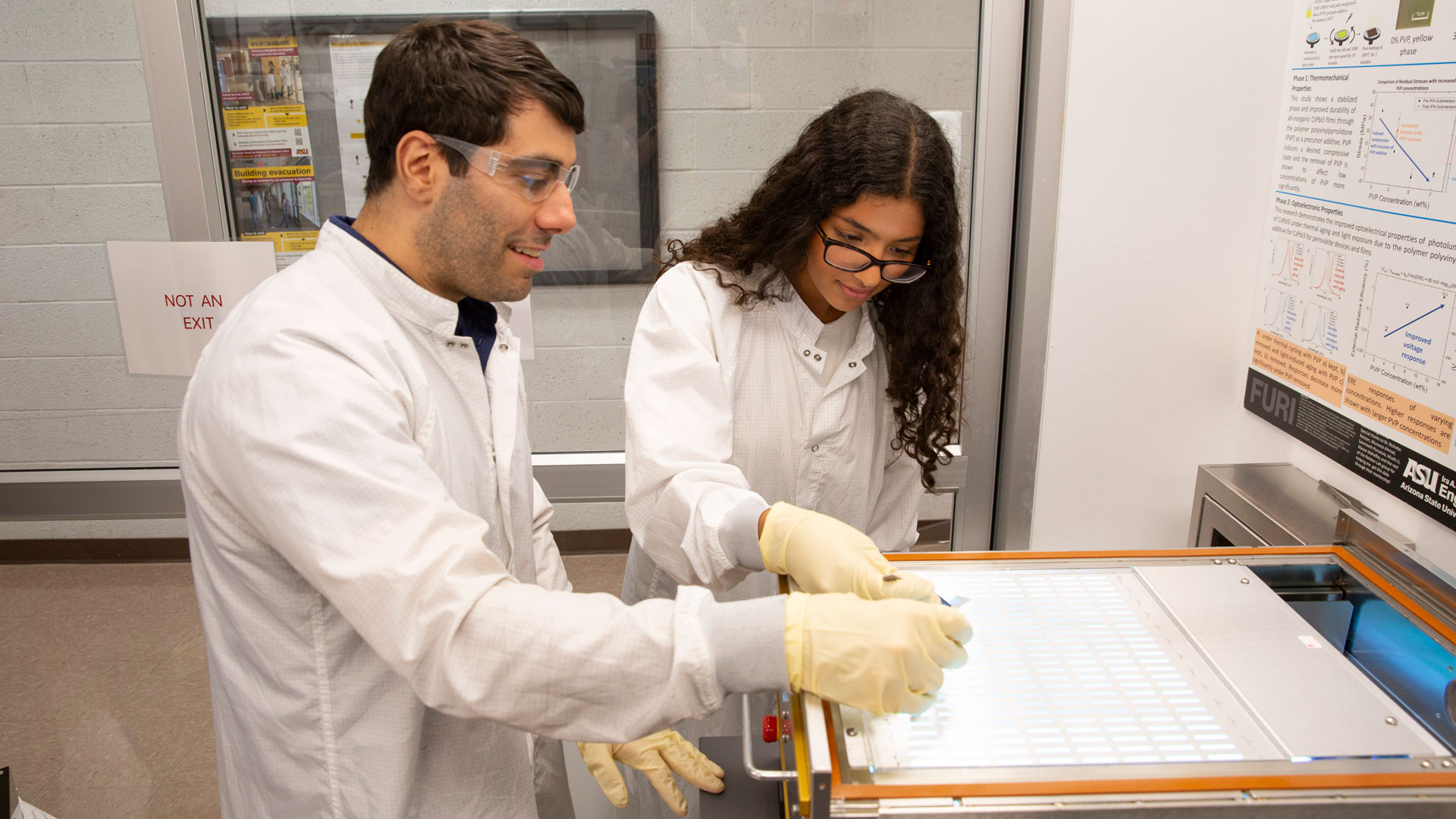

Assistant Professor Nick Rolston, a faculty member in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University, saw those traits as clues instead of deal breakers. By using the material in environments that are compatible with perovskite’s innate traits, he’s uncovering how the material can heal itself and potentially transform the durability of next-generation solar cells and flexible electronics. Perovskite’s next frontier? Space.

Rolston’s proposal to explore the potential of perovskite solar panels on orbiting satellites has been selected for the 2025 Air Force Office of Scientific Research Young Investigator Program, or YIP, award.

The honor recognizes promising early-career scientists and engineers whose work shows exceptional potential to advance basic research in support of national defense, with recipients receiving up to $450,000 across three years to pursue high-impact ideas.

Rolston plans to explore the fundamental functions of perovskite self-healing solar panels, exploring a next-generation photovoltaic material that could redefine how spacecraft are powered. His project was selected from hundreds of proposals submitted nationwide.

“Receiving this award is an honor, and it couldn’t have come at a better time,” Rolston says. “This gives us the chance to support all my students as we strive to prove this technology can make a difference.”

A material of interest

The focus of Rolston’s research is a material called a metal halide perovskite — a lightweight, flexible semiconductor with a manufacturing process similar to paint. Unlike conventional solar materials, which are rigid and can be permanently damaged by intense radiation in space, perovskites have a distinct structure. Their atoms can shift and rearrange when hit by radiation, then move back into place, essentially “healing” themselves.

“It’s not that they’re soft like clay,” Rolston says, “but at the atomic scale, these materials have a kind of flexibility so that when radiation pushes their ions around, they can relax back into their original structure.”

Rolston is exploring the theory that perovskite can survive years of harsh space conditions without the catastrophic damage that affects traditional spacecraft power systems.

Currently, most satellites rely on silicon solar cells, which are reliable but heavy, expensive to launch and vulnerable to radiation damage. As the U.S. Air Force and Space Force look for ways to power rapidly expanding satellite networks, they need materials that are lightweight, affordable, efficient and resilient.

Saivineeth Penukula, an electrical engineering graduate student in Rolston’s lab, says the project has the potential to elucidate some of the questions regarding the material.

“This technology could advance the fundamental understanding of physics in the perovskite solar cells, which is leading to this self-healing behavior from radiation,” Penukula says. “The work would also provide insights into device designs and architectures that would be favorable for the advancement of low-cost space-based photovoltaics.”

Recent studies suggest that not only does perovskite meet these requirements, it may also recover almost completely after receiving the equivalent of a decade of radiation in a matter of hours.

Rolston’s project focuses on uncovering the fundamental science behind how and why this self-healing happens. Understanding that mechanism could accelerate the design of durable, next-generation solar materials for national security missions.

Predicting the future of materials

While Rolston’s lab works with solar technologies, they spend equal attention to understanding why materials fail and how to predict those failures early.

His team uses mechanical tests, advanced imaging and reliability models to estimate how long a material might last without waiting years for real-time degradation. These accelerated tests are especially important for new materials like perovskites, which don’t yet have established qualification standards for space.

“We try to forecast a material’s future,” Rolston explains. “If we can understand how it breaks, we can understand how to make it last longer — or in this case, how to take advantage of the fact that it can repair itself.”

Solar energy is increasingly central to powering everything from homes to data centers, including the energy-intensive systems behind modern artificial intelligence. Rolston says perovskites could help meet the world’s rising energy demand by enabling ultra-low-cost, domestically manufactured solar materials.

“Imagine if making solar panels were as simple as painting a surface,” he says. “That’s the promise of this technology.”

The same characteristics that make perovskites attractive for space — low cost, efficient manufacturing and the ability to withstand harsh environments — could ultimately support the United States’ broader clean-energy and technological goals.

A marker of leadership potential

Being selected for the Young Investigator Program places Rolston among the nation’s most promising engineering researchers. The program is widely viewed as an early-career indicator of scientific leadership and high-impact innovation.

Stephen Phillips, a professor of electrical engineering and director of the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, says the technology has great potential.

“Rolston’s work to evaluate perovskite-based cell performance in space has impactful applications,” Phillips says. “The investment by the Air Force confirms their confidence in his approach.”

For Rolston, the honor reflects both the significance of his research and the strength of ASU’s rapidly growing space-power and renewable-energy research community.

“This award recognizes not just my work, but the collaborations at ASU, ASU NewSpace and beyond that made it possible,” he says. “It’s a privilege to contribute to technologies that could shape the future of space power.”